TikTok review reduced to meaningless farce

Written by

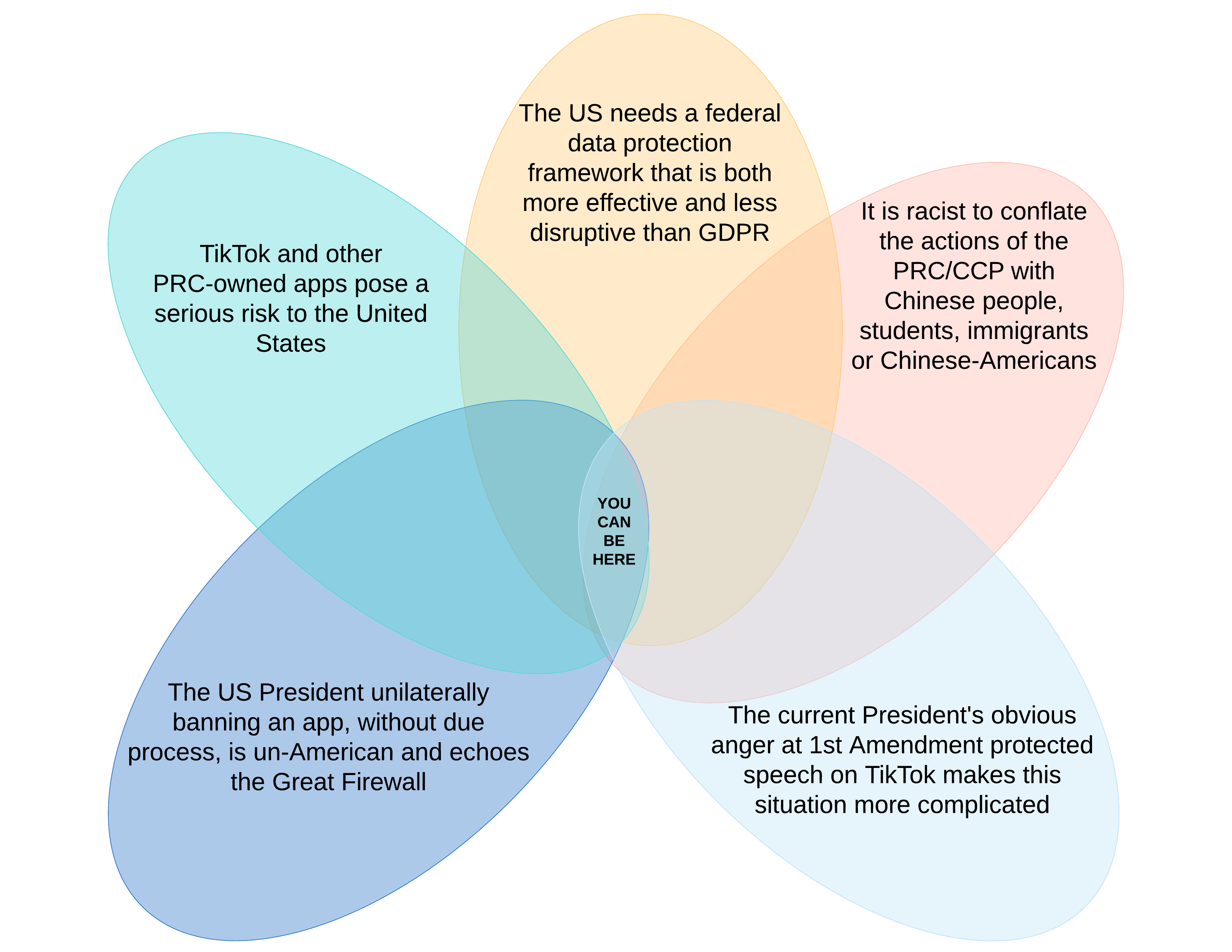

Donald Trump’s personal involvement in threats to ban TikTok is distracting from any legitimate national security concerns the video sharing app might present to the United States.

What started as some half-hearted sabre rattling after he was thoroughly punk’d by TikTok teens at his Tulsa rally in late June has spiralled into a theatre of the absurd.

The origins of TikTok’s US troubles are sane enough. The US Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) started investigating TikTok owner Bytedance in November 2019 because it didn’t seek approval for the late 2017 acquisition of a second Chinese-owned app, ‘musical.ly’. Bytedance folded musical.ly, which had a strong following among US teens, into TikTok in August 2018.

The merger of two non-US entities might not sound relevant to CFIUS, but as Bobby Chesney explains in an excellent post at Lawfare, when they do significant business in the United States, they qualify for scrutiny.

The CFIUS hasn’t released a decision on Bytedance. Typically, an adverse CFIUS finding results in hastily-arranged ownership changes by companies that want to continue to access the US market.

The idea of an outright ban, rather than a forced sale, only emerged after a disappointing turnout to Trump’s Tulsa campaign rally, where a large number of teenage TikTok users claimed to have reserved seats when they never intended on showing up.

A week after that Tulsa rally, India banned 59 Chinese apps outright, TikTok among them. India’s move emboldened a resentful Trump, and his administration started dropping hints that the US might do the same.

Flash forward to Friday night and Trump declared a barely comprehensible plan to ban TikTok in a chat with reporters on Air Force One, threatening to derail Microsoft’s plan to acquire TikTok’s US, Canadian, Australian and New Zealand operations.

In his usual, word-salad style, he said the planned Microsoft acquisition is “’not the deal that you have been hearing about, that they are going to buy and sell, and this and that. And Microsoft and another one. We’re not an M&A company”.

These words don’t sound like they are drawn from the recommendations of a CFIUS investigation.

Microsoft lobbyists earned their (presumably gigantic) paychecks over the weekend, lining up an urgent Trump call with CEO Satya Nadella. Trump has now given Microsoft 45 days to complete a deal. In return, Microsoft released a grovelling hostage letter thanking Dear Leader for his patience. The President then landed the backflip (perfect 10s!), telling reporters Monday morning that he’d prefer Microsoft buy out TikTok completely, with the US Government earning a cut of the purchase price for acting as a facilitator. It’s that wild.

Even the most ardent anti-China hawks must be perplexed by how the issue is being handled. The grounds for banning the foreign ownership of US semiconductor manufacturers (the US arm of Aixtron, Lattice Semiconductor and Qualcomm) were simple. They produce semiconductors for military and civilian government applications in the United States.

Using Chinese networking vendors (Huawei, ZTE) or Chinese carriers (China Telecom, China Mobile) in US critical infrastructure alo present supply chain risks. China’s cybersecurity laws turn Chinese-owned telecoms and telco equipment into an avenue for broad, covert collection of data by the state.

Supply chain security concerns pre-date the US campaign against China: a 2006 Check Point Technologies bid for Sourcefire was scuttled because the US didn’t want an Israeli company owning the platform with a presence deep inside US government networks.

By contrast, concerns about ownership of consumer apps typically boil down to the sensitivity of the data the apps collect. The US objected to Chinese firms owning gay dating service Grindr to (presumably) avoid the blackmail of US officials and defence personnel. It objected to foreign firms owning Moneygram due to the sensitive financial data the company holds on US citizens. The US probably objected to Chinese firms owning the StayNTouch hotel reservation system because that system stores data of obvious interest to intelligence services, including its own.

The risks presented by TikTok are less clear, but that’s not to say there’s absolutely nothing to worry about. According to its privacy policy, TikTok does store the location and contact information of its hundreds of millions of users. Citing concerns around location and contact leakage, lawmakers on both sides of US politics announced a plan to ban the app on government mobile devices. Fair enough. But teenagers, the app’s primary user base, don’t make for a great source of kompromat (unless you’re playing a super long game), and the type of data TikTok holds isn’t tremendously useful for that purpose anyway.

An adjacent (and serious) question is whether TikTok’s content moderation policies and content amplification algorithms could be used as tools to shape political discourse. TikTok has offered to expose its algorithms to reassure regulators, but it’s moderation practices have already, justifiably, raised eyebrows. As former Facebook CSO Alex Stamos illustrates, we’re in very nuanced territory here.

So, how to proceed? Matters like these need to be handled delicately. At stake are genuine questions around digital sovereignty, social media’s ability to shape discourse, state-enterprise cooperation on intelligence and the possibility of stemming the flow of investor dollars into America. It’s serious stuff. Sadly, right now it looks more like Trump is at war with America’s teenagers than with a Chinese social media company. And if he expects the ban of an app to stymie an online youth rebellion, he has a few things to learn about teenagers.

This story continues to develop at the speed of light. Within the last hour of editing this piece, ByteDance announced plans to move its operations to London, while the state-controlled China Daily is promising “mortal combat in the tech realm”.

Round one! FIGHT!