Deterrence in cyberspace isn't working. What next?

Written by

The United States is on the cusp of making far-reaching changes to how it defends its networks and projects its capabilities in cyberspace. Over the coming months, lawmakers will review the recommendations of the Cyberspace Solarium Commission - a year-long review into US cyber strategy. Will they have the nerve to push for contentious reforms, and who wins and loses in the process? Risky.Biz looks for answers in this three-part series. Subscribe to the weekly Seriously Risky Business newsletter at our SubStack page for more.

The United States long assumed that the strategic policy of deterrence that helped to keep conventional and nuclear conflict at bay would have similar results in cyberspace.

But despite its tech prowess and billions of dollars spent to stand up US Cyber Command, doubts have crept in. While there have been no ‘Cyber Pearl Harbour’ attacks, the threat of American retaliation has not deterred an ongoing campaign of Chinese intellectual property theft. It did not deter destructive malware attacks on the private sector by North Korea in 2014 or Russian election interference in 2016, and has not reigned in cybercrime directed at US citizens from Eastern Europe and Africa.

“The traditional idea of using a strong offensive capability in Cyber Command as a form of deterrence appears to have had no impact on dissuading adversary behavior in that grey zone,” laments Mark Montgomery, a former Navy Rear Admiral, during an interview with Risky.Biz.

Montgomery has just completed his first year as executive director of the Cyberspace Solarium Commission - a bipartisan effort set up to chart a change of course. It was convened at the request of Montgomery’s old boss, Senator John McCain, who recognized that lawmakers needed outside experts for some fresh thinking on how to better defend US critical infrastructure and democratic institutions from attack.

After 300 interviews, a wargame and numerous events, last month the bipartisan Commission released its report, whittling down hundreds of policy ideas to a slightly less wieldy 84 recommendations. Fifty of those were accompanied by draft bills for its two co-chairs - Congressman Mike Gallagher (Rep) and Senator Angus King (Dem) - to take to Congress.

Then came the coronavirus.

Lawmakers have since focused on healthcare and the economy. The Commission’s long-planned public hearings and launch events are postponed. Staff are running out of months to work the recommendations into law in a Congress that’s in and out of recess, and to fund a laundry list of requests amidst an unprecedented bailout of the US economy.

Somehow, political scientist Peter Singer sees a silver lining. He suspects that a post-COVID America presents the best opportunity yet to reshape cyber policy.

“The realm of possibility for many of the recommendations just got majorly widened,” Singer told Risky.Biz as the pandemic set in. “You are going to see much that was unimaginable become imaginable in a policy sense, and incredibly heightened levels of risk aversion for the long-term.”

Deterrence by denial

If the report’s great strength is the spirit of bipartisanship and openness with which it was conducted, the drawback is its broad scope. With 84 recommendations, the report can read like every party that participated was granted a wish.

Jacquelyn Schneider, a Hoover Fellow at Stanford University and a senior policy advisor to the Commission predicts that the long list of recommendations - which lacks prioritisation - might struggle to get traction “in some difficult years to come.”

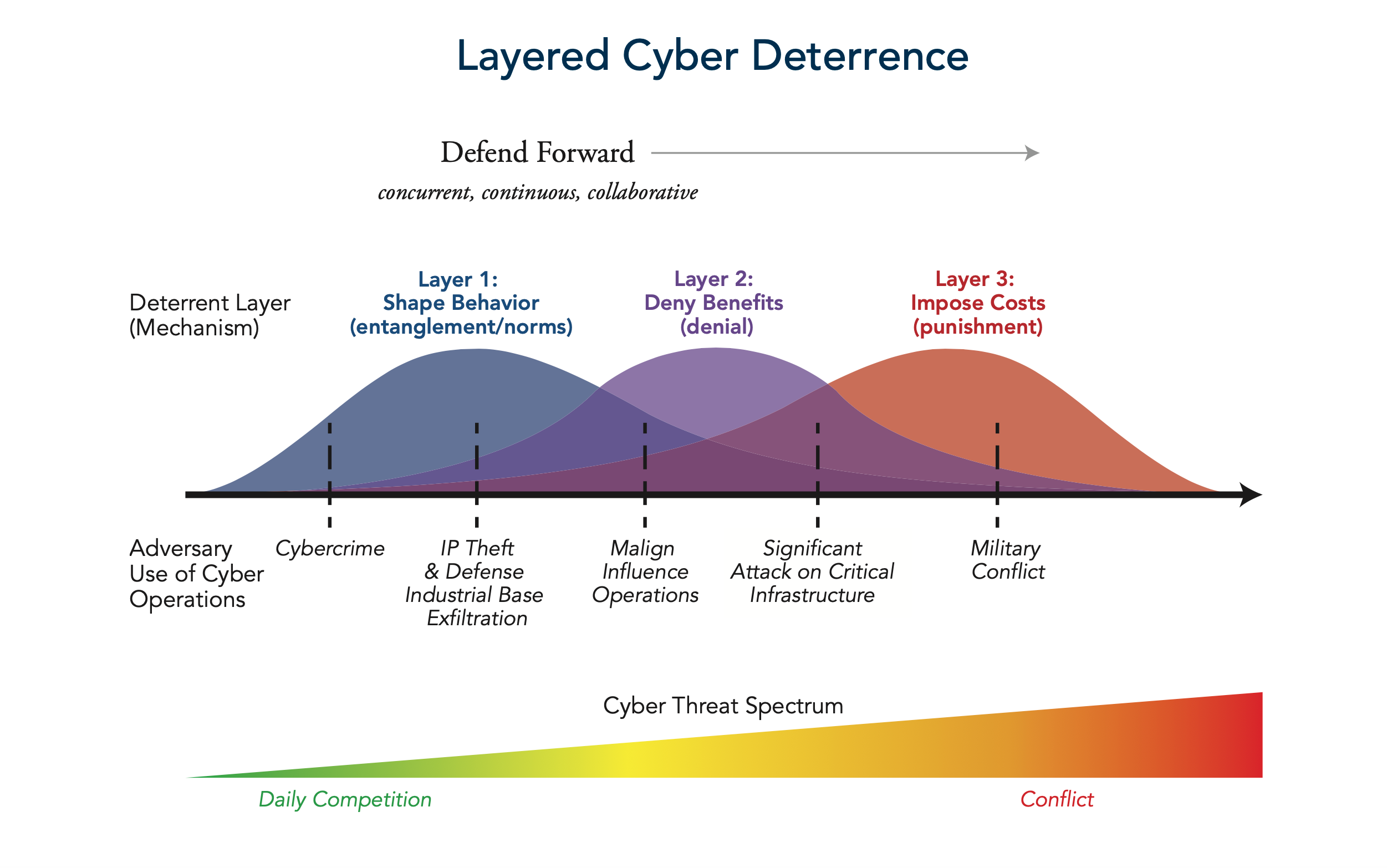

There’s no easy sound bite for a President to grasp onto. The broad-ranging recommendations are bound under a new concept of ‘Layered Cyber Deterrence’. The choice of words is revealing in itself. Wedged between the Department of Defence’s broader strategic concept of ‘Defend Forward’ and US Cyber Command’s preference for ‘Persistent Engagement’, and trying to address a problem that requires a whole-of-nation response, it almost sounds apologetic.

Deterrence can work, the commission concludes, but the US must complement the existing strategy of ‘imposing costs’ on adversaries with one of ‘deterrence by denial’.

So while it continues to recommend the US actively engage and disrupt malicious activity in adversary space (‘Defend Forward’), the Commission seeks legislative change and funding to improve the defence of critical infrastructure in order to ‘deny benefits’ to attackers.

Pragmatism over prioritisation

While ‘deny benefits’ is the Commission’s top recommendation, the recommendations that support it won’t be the first change put to lawmakers.

The Commission opportunistically views the next NDAA bill - which was supposed to be tabled in April - as the legislative vehicle to fast-track those recommendations that “primarily deal with the Department of Defense.”

The National Defence Authorizations Act is the means by which Congress annually tops-up the Defence budget - and is as close to a ‘sure thing’ to pass each year as any other bill.

“We are moving full speed ahead to try to incorporate as many of the recommendations as possible into the NDAA,” Representative Gallagher told Risky.Biz in a written statement.

The most contentious of the issues to be explored via this process relates to what budget and authorities are granted to US Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM). The report calls for a ‘force structure assessment’ of the Cyber Mission Force.

Today Cyber Command is a unified command of the DoD, rather than its own autonomous branch. The funding allocated to it is drawn from the cyber operations of the Army, Air Force and Navy.

(To illustrate, the proposed FY21 budget for the DoD allocates US$2.2 billion to Cyber Command from a total of US$3.8 billion spent on cyber operations across DoD. The Commission subsequently recommends Cyber Command be designated for Major Force Program Funding in the FY21 NDAA bill. This would give Cyber Command the autonomy to, for example, independently acquire its own technology rather than through the Armed Services.)

Today, the Armed Services have committed 6,200 personnel to Cyber Command - a number pegged in 2014. Montgomery expects that an independent ‘force structure assessment’ of the Cyber Mission Force would be likely to recommend a “significant increase” in personnel for Cyber Command.

Schneider expects the Armed Forces to reflexively be hesitant, if only due to organisational bias.

“There is a very strong argument for cyber security to be a greater component of Department of Defence spend,” she said. “But telling the DoD to invest more in cyber security will be a tough sell at a time the Defence budget is more than likely going to be cut.”

The Armed Forces are already asked to give “their most qualified people - the people that provide support to warfare” over to Cyber Command, she said. And unlike the contributions they make to rotating combatant commands, these forces don’t necessarily return.

“They would naturally prefer that talent be used to take down enemy air defence systems or disrupt counter-insurgencies than to protect critical infrastructure.”

This is why Cyber Command needs Congressional support for any increase in commitment, Montgomery noted. The Armed Services would view any such increase as “coming at the expense of a ship, a squadron of aircraft or a battalion.”

“In the absence of an objective, accurate, up-to-date force structure assessment, they are not going to willingly increase their commitment from a force of 6,000 on-net operators to perhaps 10,000 or 11,000 based only on a request from Cyber Command,” he said.

Signalling as a form of deterrence

The Commission also calls on the Executive Branch to play a bigger role in ‘signalling’ what actions the US Government is prepared to take against attacks that fall below the threshold for use of force, but above a threshold that damages the national interest.

“There are a number of recommendations the executive branch could action immediately, including getting to work on an updated National Cyber Strategy that reflects the Commission’s approach of layered deterrence,” Gallagher said.

Writing for Lawfare, Commission Senior Director Dr. Erica Borghard argues that ‘signaling’ is a missing piece in the Defend Forward Strategy.

“Under ‘Defend Forward’, the United States is assertive,” explains Lauren Zabierek, Executive Director of the Cyber Project at Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center. “Rather than passively waiting for or allowing for operations against us, the idea is to lean forward into adversary spaces and dismantle, disrupt or degrade their efforts before they attack. If you’re going to Defend Forward, signalling might help to reduce the potential for escalation. It otherwise can be hard to determine intent in cyberspace.”

Assume, she said to illustrate, that a collection operation goes wrong or has unintended consequences. It is difficult to convey to another nation in the heat of the moment what the original intent was, especially if the other nation is an adversary you aren’t on great terms with.

Any public declaration of how you would respond to a given ‘red line’ has its risks - it must be an action you are prepared to take in order to remain credible, she said.

The US is in a tight spot, according to Dmitri Alperovitch, former co-founder and CTO of Crowdstrike, who was briefly brought in to the Commission to play the part of a ‘Red Team’ adversary in a wargame exercise.

“When an adversary reaches the level of use of force, decisions are relatively easy. When your people are dead in the streets or when critical infrastructure has been disabled or destroyed, that is when the cyber guys are told to sit in the corner because the planes and the missiles are taking off. At that point we are at war and we know what to do.

“The challenge is that most cyber attacks never get to that level. Virtually all of the attacks that we see in the cyber domain fall below the threshold for use-of-force, but above the threshold in which we do experience some pain that can’t be ignored. We are not going to put lives at risk by going to war over someone destroying 30,000 computers. So we are having a hard time trying to figure out what responses would be sufficiently painful to convince our adversaries to stop.

“Any response below the threshold of use of force to date has failed. Personally I don’t believe you can effectively deter the nation-state adversaries that we face in this domain with a cyber response.”

There isn’t yet much research to suggest that the subtle forms of signalling used to date - the use of sanctions, public indictments and public dumping of adversary malware - has had significant impact.

“Our adversaries have acted with impunity,” says Zabierek. “[But] we should keep in mind that this is still a relatively new domain - and we’re still evolving policy and strategy.”

Zabierek nonetheless agrees with the need for a new declaratory policy, if only because it demonstrates coordinated thinking and national resolve.

According to Commission co-chair Senator King, effective signalling requires leadership from the highest office. The Commission recommends that a Senate-confirmed National Cyber Security Director be appointed in the President’s Executive Office - an officer with an ‘access all areas’ pass to coordinate US policy. This Director’s role would include ensuring responses to adversary aggression would - in Senator King’s words - be “fast” and “sure”.

The appointment of a cyber tsar is also among Montgomery’s top three priorities. The late US response to the Coronavirus pandemic has given him even more resolve to get it done. He notes that while Dr Anthony Fauci and Dr Deborah Birx have played important roles in coordinating a national response to the virus on President Trump’s COVID-19 Task Force, they only gained that authority after the pandemic hit. Ideally, there should have been somebody with a White House pass appointed well in advance of a pandemic arriving to prepare for such an event.

“In my mind, a National Cyber Director would be positioned to prepare the government and ensure we have the most rapid and effective incident response in place when there is a major cyber infrastructure event in the future,” he said.

The appointment would require both the legislative branch to pass a law to create the position and the executive branch to empower the nominated individual.

A further recommendation - that Congress form dedicated House Permanent Select and Senate Select Committees for Cybersecurity - also requires the support of both branches. Today, cyber security is covered in numerous committees - providing limited opportunities for lawmakers to specialize in the issues. Collapsing these matters into dedicated committees will be an uphill battle - fellow Solarium Commissioner Congressman Jim Langevin (Dem) described the recommendation as a “marker” of something Congress should do - recognising that the dozens of representatives that might feel like they are losing access to cyber security expertise are unlikely to take the news lying down.

Alperovich expects similar results across a range of recommendations that deal with machinery of government. By including current government officials on the Commission, it “probably limited their room to maneuver and try to resolve some of the more thorny bureaucratic issues”, he said, which “remain largely unresolved by the Commission.”

Fast and sure

The Commission also asks the DoD to review whether cyber operatives in Cyber Command, the NSA and other offensive security units have been granted the necessary authority to act nimbly against adversaries when required.

Under the previous (Obama) administration, any cyber operation above the level of collection required White House permission, limiting the ability to respond to threats in real-time.

“If it is easier to kill someone with a drone strike then two than to destroy a data file on someone’s computer, you know that you’ve got your priorities messed up,” Alperovitch said.

To its credit, the Trump administration - backed by Congress - has come a long way in streamlining this authority. In 2018, Trump signed the National Security Presidential Memorandum (NSPM) 13, which allows for the Secretary of Defense to sign off on ‘time sensitive’ offensive cyber operations. Shortly afterward, the 2019 NDAA defined cyber surveillance and reconnaissance as a traditional military activity - giving Cyber Command express permission to hunt for threats outside of .mil networks.

The Commission now wants to know if that’s sufficient. Using an analogy from conventional warfare, Zabierek explains that large kinetic operations would usually require authorization from the top of the chain of command, but has to also allow for skirmishes at the tactical level.

“Military scholars acknowledge that there is constant contact with adversaries in cyberspace,” she said. “In certain circumstances our cyber forces should be allowed to engage with that adversary without waiting for the chain of command outside of Cyber Command to weigh in.”

Montgomery cautions that it shouldn’t be taken as a foregone conclusion that current authorization processes aren’t sound.

“We’re only asking a question, not asking for change in law,” he said. “Standing rules of engagement tend to only get reset every decade, and maybe amended once in between. To implement Defend Forward, we need to make sure we aren’t putting any inappropriate constraints on Cyber Command’s ability to respond. So we are asking whether the time-lag required to get authority is acceptable. Are decision-making authorities set at the right level? We’re asking for the DoD to determine whether there is any unnecessary friction that delays rapid and cohesive action.”

Hunting on defence contractor networks

Another recommendation that could fall within scope of the NDAA is a requirement for defence contractors to allow DoD to perform or commission threat-hunting on their networks.

The US Defense Industrial Base has been heavily targeted by adversaries, and it’s track record isn’t stellar. Consider the theft of F-35 plans and undersea missile technology - not to mention the Snowden leaks.

The Commission felt it was no longer sufficient to simply ask defence contractors to attest to their own security. “Some of these companies clearly don’t have the capability and capacity to detect adversary behaviour on their systems,” Montgomery said.

The scope of the threat-hunting, he said, would likely be limited to searching for known adversarial behaviour on the “infrastructure that relates directly to their work with the government”.

“I think this is a reasonable request of companies that profit greatly from participating in Defense contracts,” he said.

Schneider agrees, with some qualifications.

“Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Raytheon - they are already very used to the Government being up in their business,” she said. “But there is a category of supplier Defense wants to work with where it might cause friction. If this requirement were to be extended to Silicon Valley companies that would ordinarily cater to commercial clients - that’s a tough road. There might need to be a flexible approach.”

Next steps

The process for marking up the next NDAA bill began back in March, but by April it became clear that it would be postponed to allow the administration and the DoD to respond to the coronavirus outbreak. It may now be delayed until as late as October.

The only good news from the delay is that the Commission staff now have several months more than originally planned to peddle recommendations to lawmakers and the Executive Branch.

Representative Gallagher remains optimistic that the report will be as relevant then as it is today.

“My colleagues — Democrat and Republican alike — have been very supportive of the Commission’s work, both before and after the Coronavirus outbreak,” he said. “If anything, our response to the pandemic has highlighted just how important it is to have coherent continuity of economy and continuity of government plans in place in response to a crippling national crisis. I’ve been asked whether the virus has given the Commission cause to highlight and even revisit certain recommendations.”

Pt II of our feature on the Cyberspace Solarium Commission will discuss recommended reforms to securing the .gov space and new security regulations over the private sector.